February 12, 2026

Local Agents of Change: Designing Leadership at NuVu

At NuVu, making something is never the end of the story.

In Local Agents of Change, Coach Heide Solbrig’s latest studio, students weren’t just building projects. They were building the capacity to lead.

“This is really about connecting the dots between: I make a thing, and I go out in the world and am a leader about making things,” Heide explains.

The studio is structured around Marshall Ganz’s model of public narrative—Story of Self, Story of Us, and Story of Now—a leadership framework taught at Harvard’s Kennedy School. It may sound abstract, but in practice, it’s deeply personal and highly practical.

Heide sums it up as head, heart, hands.

- Head: What do I understand? What systems am I analyzing?

- Heart: What do I care about? Why does this matter to me?

- Hands: What am I actually going to do about it?

That combination—thinking, feeling, doing—is what transforms a project into leadership.

Story of Self: Where Leadership Begins

The studio began with an unusual assignment: students created a “personal inventory” and told a story about themselves.

By the time students are teenagers, Heide notes, they’ve experienced events that shaped them—moments that are meaningful, formative, even traumatic. Many students found themselves reflecting on education itself: learning differences, school transitions, moments of struggle or breakthrough.

They recorded these stories. They revised them. They gave and received feedback.

Then came the harder part: connecting those stories to something they care about in the world. “That’s actually really challenging,” Heide says. “I care about this stuff—how do I decide to make a thing?”

That leap—from identity to action—is what Heide explains is the foundation of leadership.

Story of Us: Building Community

From there, students researched organizations, met community members, and explored how people organize around shared commitments.

For some, this meant pushing existing projects further.

Lloyd, who has spent years building the NuVu Combat Robotics League, used the studio to think more critically about community. How does he acknowledge its limitations? What resources does it need? How can he make it more inclusive and sustainable?

Rather than simply running events, he began thinking like an organizer—someone building infrastructure and asking others to join.

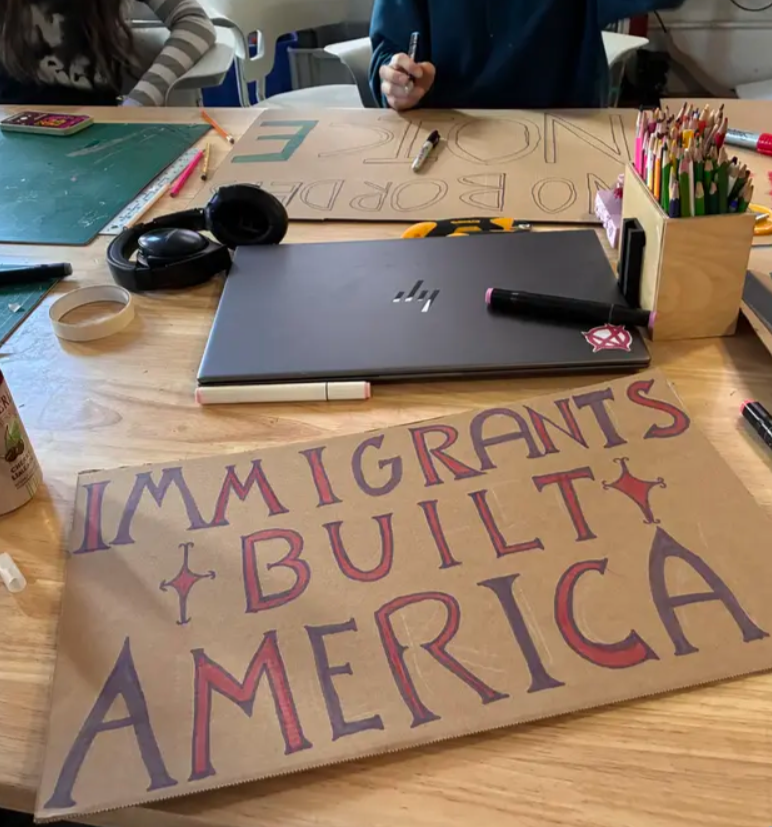

Other students leaned into activism more directly.

Sam and Vexx organized a teach-in around immigration enforcement, attended a vigil, and hosted a sign-making event. The first event drew only a handful of participants. It was discouraging.

That moment became part of the learning.

“Activism is hard,” Heide says. “You tell your friends, and only one or two show up. And you have to keep going.”

When they tried again, more people came, and they considered that second event a success.

In that process—disappointment, recalibration, persistence—students encountered leadership not as an abstract concept, but as lived experience.

Story of Now: An Urgent Call

By the final weeks, students were ready to design their “urgent call”—a public-facing project that connected their personal story to a present need.

Scarlett, one of our Beaver students, drew from her experience with dyslexia and interviewed teachers and peers about learning differences. Her writing will be published in the school paper, and she is developing a series focused on how schools support (and sometimes fail) neurodiverse learners.

Kaia, whose mother is undergoing cancer treatment, chose to organize a fundraiser connected to a cancer organization that has supported her family. She’s coordinating directly with fundraising directors to build something sustainable and meaningful.

These projects vary widely in topic and format—video, journalism, organizing, event design—but they share a common structure: they are rooted in lived experience and directed outward.

Students are not simply expressing themselves. They are asking something of their community.

Designing Leadership

For our senior students, the studio serves as a precursor to Capstone. Heide points to Jade, who began exploring open-source medical devices in this course last year. The relationships and clarity she developed here propelled her into a year-long project connected to professionals in the field.

That’s the power of the structure.

By practicing public narrative—by articulating why they care, who they stand with, and what must happen now—students begin to see themselves as agents rather than observers.

They learn that telling a compelling story can mobilize people.

Most importantly, they learn that their voice carries weight.